The Case for Christian Nationalism

Introduction: The Great Renewal | V. Summary of Argument and VI. Foreword

Previously:

The remainder of the chapter is a summary of arguments that the brunt of the book will handle in depth, so I will comment on individual statements that I find of note and summarize planned counter arguments.

Adam’s original task, his dominion mandate, was to bring the earth to maturity, which served as the condition for eternal life.1

We should pause when we come across the word “dominion” in Christian Nationalist writings, because it often is used in a militaristic fashion. Adam’s “dominion… over all the earth” (Genesis 1:26) is the proper categorical description of his sum position as image bearer and garden tender. But perfect obedience to God in all things, not just successfully exercising dominion, served as the condition for eternal life under the covenant of works. In Scripture, the condition is expressed in the negative, when God commands Adam not to eat of the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil (Genesis 2:16-17). This could be dismissed as a simple misunderstanding or uncertain phrasing if taking dominion was not a major theme of this book - it is what Wolfe considers man’s secondary telos.2

Wolfe’s idea of multiple, pre-fall nations returns, and the main rebuttal will be saved for later, but it is of note that he seems to build his whole hypothesis forgetting that God walked among prelapsarian man (Genesis 3:8).

The instinct to live within one’s “tribe” or one’s own people is neither a product of the fall nor extinguished by grace; rather, it is natural and good.3

Wolfe has a history of not only promoting his “tribe”, but also denigrating other “tribes”, which colors everything he says on the subject and may be a motivation for his conclusions.4 He later bolsters his goodness of tribes claim with the statement that “there is no universal language”.5 Scripture tells us that, several generations after the flood, “the whole earth had one language and the same words,” and that God purposefully separated man into disparate languages and cultures to limit his attempts to place himself on par with God (Genesis 11:1-9).

… much good would result in the world if we all preferred our own and minded our own business. (emphasis mine)6

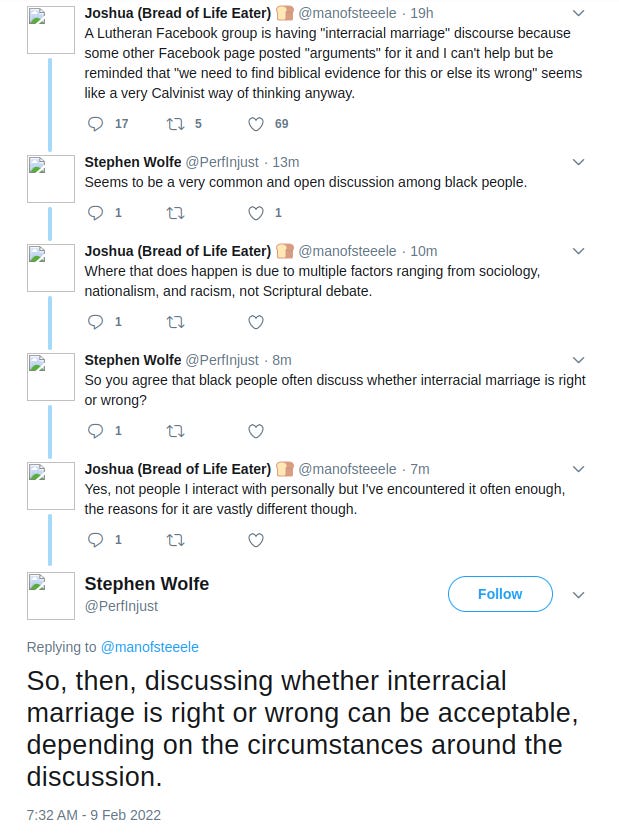

This is the exact phraseology a Klan member or Neo-Nazi would use, and if Wolfe does not want to be seen in that light, then he should either not write in this way or go to great lengths to explain exactly what he means here (he does not). Though Wolfe promotes a heterodox definition of ethnicity as culture more than genetics7, that definition would still fall under the bounds of “our own”. That means, with this sentence, his theory has unequivocally become ethno-nationalist - and notably similar to the Falangist view of cultural “Spanishness” under the unidad de destino en lo universal (unity of destiny in the universal).8 It is worth questioning, given what Wolfe has said about intermarriage in the past,9 whether he thinks of White and Black American cultures as potentially different ethnic nations, under his theory. That he followed his podcast cohost’s explicitly white-nationalist, anonymous accounts on both Twitter and Facebook, where racial slurs were flung, serves as more circumstantial evidence to that end.10

Continuing on the theme of preferring our own, Wolfe gives an endorsement for “complacent love”, the “pre-rational preference we have for our own children, family, community, and nation.”11 Most of note, in nearly a page on supposedly “Christian” love, is the total absence of the person of Jesus Christ. Rather than encouraging us to lean into our natural love feelings, He challenges us to turn our conception of love on its head (Matthew 5:43-45), and requires us to eschew our “pre-rational preference” in order to love Him first and foremost (Matthew 10:37).

A supernatural conclusion can follow from a natural principle when it interacts with supernatural truths.12

Given god’s sovereignty over His creation, the natural principle is inconsequential in this equation. Many well-functioning nations have striven to direct people towards what they believed was the true religion, when it was actually false religion. The pagan empire that Peter instructed Christians to be subject to was one of the largest and best-functioning nations the world had ever seen (1 Peter 2:13-14). Supernatural truths are not pantheistic properties waiting to be interacted with, should we collectively orient ourselves in the proper direction. It is only those to whom God has chosen to reveal Himself that have any hope of applying natural principles towards heavenly good (Ephesians 1:11). Saul was working against the principle of “[directing] people to the Christian religion” when he was confronted with, and redirected by, supernatural truths (Acts 9:1-5). From Whom do natural principles come, and how/where would we confirm them as natural principles? Wolfe may agree with all of this, and it may seem like splitting hairs, but our utter dependence on God is not a small, theological matter. Continued insistence on a foundation of natural principles that orient us towards God minimizes the necessary epistemological starting point of God revealing His will to fallen man.

Following this, Wolfe praises the goodness of a cultural Christianity that has the under-girding of genuine faith13, an assessment that is hard to disagree with. Even today, our highly polarized society is held together by the shadow of the Overton window of the Christian ethic; it is that powerful and beneficial.

Laws can also penalize open blasphemy and irreverence in the interest of public peace and Christian peoplehood. The justification for such laws is not simply that God forbids these things in the First Table of the Ten Commandments, but that they cause public harm, both to the body and the soul.14

I will argue, when this case is made in depth, that the New Covenant explicitly tells the Christian to leave blasphemers in peace (2 Timothy 2:24-26, 2 Corinthians 10:3-6), and since, as Wolfe admits, man is only bound by (and the government can only enforce) God’s moral law as revealed, a Christian government would violate the Second Table if it used the sword to punish the thoughtcrimes of “blasphemy and irreverence” (not to be mistaken with the Second Table violation of vulgarity). A question that must be asked of those promoting this type of First Table enforcement is, “What happens to the Mormons and Jehova’s Witnesses who won’t stop evangelizing?” Wolfe will answer that question in a way that most Western Christians will likely find unacceptable.

Our time calls for a man who can wield formal civil power to great effect and shape the public imagination by means of charisma, gravitas, and personality.15

It is telling that Wolfe instructed us in preceding sections to not compare his theory to previous nationalist and fascist thought, when he has yet to deviate from an iota of it. Are we to ignore that he is now arguing for a Protestant Caudillo? There will be much more to say about this when we reach chapter 7.

Arguing for violent revolution:

If [a ruler’s] commands harm them, they can depose or remove him and enact better arrangements. National harm can include oppression against true religion, and thus the people can conduct revolution in order to restore true religion.16

This is far from universal, 16th and 17th century Reformed thought. The 16th century, Swiss theologian and friend of John Calvin, Pierre Viret, considered a reliable peacemaker when these types of issues arose, wrote, “And if the magistrates do not fulfill their duty but are instead tyrants and persecutors who uphold the cause of the wicked and persecute the children of God, we must leave the vengeance of such tyranny and iniquity to God.”17

But there are many misunderstandings today concerning what Protestants once believed about the role of civil government with regard to false religion.18

Wolfe uses this as an appeal to tradition/authority logical fallacy. Some Protestants once believed the role of civil government with regard to false religion included the burning and drowning of Anabaptists and the drawing and quartering of recalcitrant Catholics. Even then, there was far from a great consensus, among the varying 16th century Protestant city-states, on how to deal with heresy, especially with Anabaptism. While Basel, Zurich and Berne regularly executed Anabaptists, the only person ever executed for heresy in Geneva was killed for publicly denying the Trinity.19

Thus, chapter 9 shows that the religious toleration in the founding era was rooted, not in Enlightenment thought or liberalism, but in good Protestant principles applied in light of Anglo-Protestant experience. Early America is a Protestant resource for an American return to Christian nationalism.20

Wolfe touches on a subject that very few Americans know about, and which he can mythologize to a general audience, as many others have. Common to colonial law was the fining of Catholics for not attending Protestant services and banning them from owning property.21 One would be hard pressed to find modern, conservative, American Protestants willing to return to the colonial charter system, where the governor often had the responsibility of making sure no pastors of competing Protestant denominations, to the state denomination, were allowed to plant a church.22

The chapter ends with an appeal to a “national desire” for “our homeland and its people”.23 Of great note throughout this chapter are the ubiquitous, emotional appeals to a sense of “home and hearth”. Given that the ten-thousand-foot view of Wolfe's philosophy has no distinguishing characteristics from previous nationalist, and even fascist, thought, these regular appeals to ethno/cultural collectivism are especially striking.

Next:

Stephen Wolfe, The Case for Christian Nationalism (Moscow, Idaho: Canon Press, 2022), 21.

Ibid., 21.

The Westminster Shorter Catechism’s very first question defines man’s telos as “to glorify god and enjoy him forever”. I will later argue that a caring dominion over the earth is a means to that telos, not the telos itself.

Stephen Wolfe, 23.

Stephen Wolfe, 24.

Ibid., 25.

Giorgia Priorelli, Italian Fascism and Spanish Falangism in Comparison: Constructing the Nation, Palgrave Studies in Political History (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), 144, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-46056-3.

“On Thomas Achord”, Alastair Roberts, https://alastairadversaria.com/2022/11/27/the-case-against-thomas-achord

Stephen Wolfe, 25.

Ibid., 27.

Ibid., 28-29.

Ibid., 31.

Ibid., 31.

Ibid., 34.

Peirre Viret, When to Disobey, ed. Rebekah Sheats and Scott T. Brown, 1st edition (Church and Family Life, 2021), 7-9, 37.

Stephen Wolfe, 34.

Matthew J. Tuininga, Calvin’s Political Theology and the Public Engagement of the Church: Christ’s Two Kingdoms, Cambridge Studies in Law and Christianity (Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 78.

Ibid., 36.

Ray Allen Billington, The Protestant Crusade,1800-1860, First Paperback (Chicago, Illinois: Quadrangle Books, 1964), 6.

Michael Williams, Shadow of the Pope (New York: Whittlesey House, McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1932), 14.

Charles Lee Raper, North Carolina: A Study in English Colonial Government, Library of American Civilization (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1904), 31.

Stephen Wolfe, 38.