Am I a Christian Nationalist?

I Answer the questions from the latest, more nuanced study by Neighborly Faith

Neighborly Faith, an organization founded to help evangelicals form stronger relationships with people of other religions, released a new study that claims to “more precisely gauge [Christian Nationalism’s] prevalence and identify the specific threats of CN for American society.” They say they have achieved this by asking more questions than other studies, such as the five questions asked in a study released in February by the Public Religion Research Institute. Here, I will answer Neighborly Faith’s fourteen question survey to gauge whether I, someone who wrote a book refuting a popular form of self-described Christian Nationalism, am, in fact, a Christian Nationalist (or “sympathizer”) myself.

1. The true culture of the United States is fundamentally Christian.

Agree? At least the founding culture was. Nearly every colony was chartered along religious lines and had an official state church. I detail in my book how that caused major issues, especially the persecution of Catholics well into the 19th century, but it is fundamentally true that the overwhelming culture of the United States was Christian until very recently (probably until roughly fifty years ago). So, what does Neighborly Faith mean by “true” here? One can believe in the separation of church and state, while still believing that we have lost our moral compass, and wish for a cultural shift back to Christian mores.

2. The federal government should declare the United States a Christian nation.

Disagree. Christian nations are those with a plurality of Christians, who have decided to recognize themselves as such. A majority of Americans do not even believe that Jesus is God; it would be ridiculous for us to declare ourselves a Christian nation at this juncture. Also of note is that such a declaration does not require the prohibition of the public practice of other religions. Complete freedom of religion was the state of the Christian empire of Rome in the 4th century, under Constantine.

3. The success of the United States is a critical part of God’s plan.

Strongly disagree. The United States is just another nation and can rise or fall, as part of God’s providence. Agreement is not a position of all Christian Nationalists, though. Stephen Wolfe, the author of The Case for Christian Nationalism, would also answer no to this question.

4. The federal government should advocate uniquely Christian values.

Strongly agree. What genuine Christian, who believes that Scripture is God’s special revelation to the world, detailing beliefs and behaviors for the most commodious life, would not want those values advocated for by their government? Would even liberal Christians, who do not believe in the inerrancy of Scripture, still not want adulterers to be treated by the example set forth by Christ (John 8:2-11), as opposed to how they are dealt with in Muslim nations? Here, though, I stand in direct opposition to self-described Christian Nationalists, such as author of The Statement on Christian Nationalism and the Gospel and Oklahoma state senator-elect Dusty Deevers, who wants to institute the public shaming of adulterers.

5. We who live in the United States have a moral obligation to face its shortcomings and try to do better.

Agree. This is the duty of any citizen of a republic. This does not seem like a question that has anything to do with Christian Nationalism, unless they want to filter out people who are so bought into the culture war that they have shut themselves off to the most basic critical reasoning.

6. We live in a nation of laws, even laws that are not consistent with my faith, and people should respect them.

Neither agree nor disagree. We live in a republic where the majority of citizens do not hold church membership and, therefore, laws will be passed that are not in direct alignment with the Christian faith. We are duty bound to respect them unless they directly contradict the explicit commands of Scripture. God’s Law must come first to the Christian, which is why we must also consider ourselves sojourners and exiles in this world.

7. Faith can make people better citizens.

Strongly agree. What Christian does not believe this?

8. Christian symbols, like the cross, the Bible, or the Ten Commandments, should be the only religious symbols allowed in governmental buildings.

Strongly disagree. We are not an explicitly Christian nation. One could ask this question alone as a solid bellwether of a person’s status as a Christian Nationalist, because this is actually a stated goal of all sub-genres of the movement.

9. In allowing different kinds of people to live in the US, the Federal Government is promoting divisiveness.

Strongly disagree. We have been dealing with this issue, in one form or another, for over two centuries. If you are a white American, chances are you have an ancestor who immigrated within the last century and a half, and who was considered to be a person of an ingrained lower character that was “incompatible with American values,” yet your family (presumably) assimilated just fine.

10. The federal government should allow all faiths to display religious symbols in public spaces.

Agree, to this inversion of question 8, with caveats. No public displays of religious symbols should explicitly threaten other faiths. For example, a Muslim display of religious symbols should not be accompanied with a statement about intifada revolution, any more than a Christian display should not talk about banishing or executing proselytizers of other religions, which is a policy position of Wolfe’s brand of Christian Nationalism.

11. Public schools should allow teachers/coaches to lead or encourage students in Christian prayer.

Agree. What they should not allow is teachers/coaches to pressure or force students to join in Christian prayer. The Supreme Court agrees, determining that a football coach in Washington was allowed to pray on the football field after games. This is a form of encouragement that would turn into leading prayer, should students join him.

12. Religion has no place in government.

Strongly disagree. Religion—I believe the Christian religion—is the sole source of absolute truth and morality. Without an absolute lawgiver there can be no actual law, only competing, subjective interests. Religion, therefore, serves as the basis for all just law. I can recognize that others disagree with this assessment, and allow for their dissent within the halls of government, while vigorously disagreeing with them. This does not make me a Christian Nationalist.

13. I would prefer if someone from my own faith tradition was elected president of the United States.

Strongly agree. Would an atheist not prefer an atheist president? Would a Muslim not prefer a Muslim president? We can all agree that there should be no religious test to qualify for office, while still preferring that someone who shares our religiously inspired social mores holds that office. What a ridiculous question.

14. The federal government should enforce strict separation of church and state.

Neither agree nor disagree. It depends on what “strict” means. If it means answering no to question 11, then obviously I would answer no to this question. If it means that the government should not name an official state church, then I would answer yes. “Separation of church and state,” to the fervently anti-Christian side of this debate, has come to mean denying Christians the right to advocate for laws that adhere to their social mores, something that every demographic has the right to do in our republic, and is the whole point of the project. In that respect, they are just as much religious extremists as Christian Nationalists.

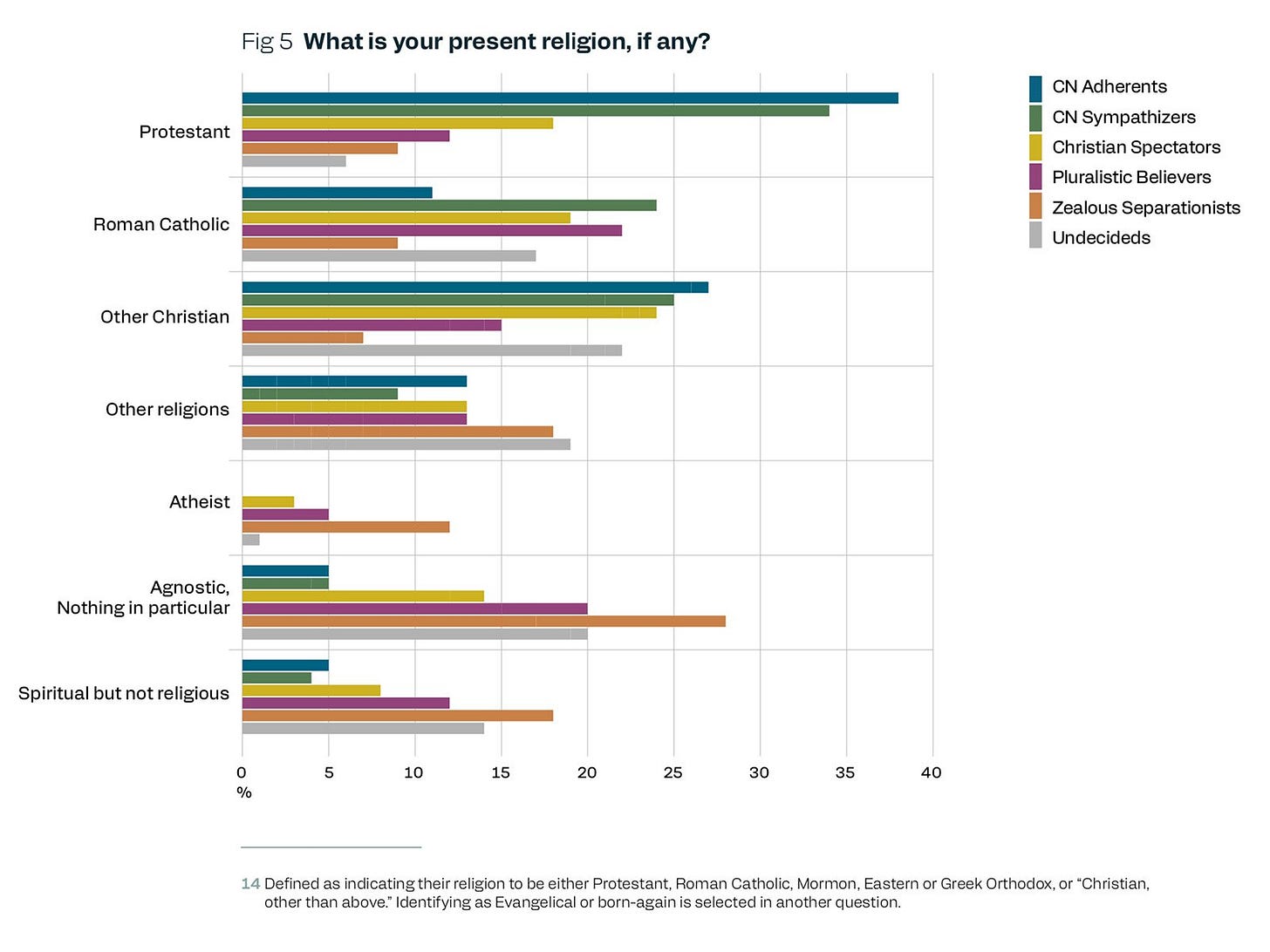

Given my answers to these questions, and that Neighborly Faith strangely categorized five percent of agnostics and non-religious spiritualists as “CN Adherents” (see the figure below), I very much suspect that they would categorize me as at least a “sympathizer” to Christian Nationalism. I am well-known among self-described Christian Nationalists as opposed to their project, and near-ubiquitously regarded by them as an enemy of the church. Therefore, it would seem that these studies still have a lot of work to do in their categorical determinations.